The following article by George Smith captures life at one of Maine’s heritage sporting camps…100+ year old Bradford Camps:

David has hunted and fished all over the world, but Bradford Camps on Munsungan Lake is the only place he’s returned to, and he often comes here several times a year.

The six hour drive from my home to the camps went quickly, with my friend, long-time now-retired guide Gary Corson, in the passenger seat. We shared stories and talked about fishing issues all the way, with one stop at Dysart’s for a great breakfast.

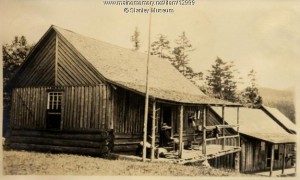

As we drove into the yard at Bradford Camps, we stepped out of the vehicle and back in time. Log cabins dotted the shoreline, made from logs that were floated across the lake more 100 years ago. In all that time, the camps have had only five owners. Igor and Karen Sikorsky knew immediately, after searching the state for years, that these were the camps for them, and they’ve been providing the age-old sporting camp experience for 20 years.

Igor is well acquainted with the sporting camp experience because he started going to Cobb’s Pierce Pond Camps when he was 10. Traditions are important at sporting camps. I loved Karen’s story about the lodge’s beautiful living room. She and Igor moved the furniture around and long-time guests objected!

On the wall of the lodge, I recognized the famous photo of Will Atkins with a canoe full of moose heads. Atkins built the original camps here in the 1800s. And while the camps retain the old, including the gorgeous log siding, they offer modern day comforts including full bathrooms in each cabin. Gas lights and instant hot water are nice features, too.

Our cabin #5 had two large bedrooms and a gathering room with a wood stove. The windows looked out on Munsungan Lake and the mountain beyond. Chad, who helped us move our gear into the cabin and has worked here for 20 years, already had a fire going and the cabin, on this cool rainy day, was nice and warm.

When we first arrived, we walked to the lodge, where guests were eating lunch. Within 10 minutes, we’d met and been welcomed by Igor, Karen, all the staff, and even all the guests! Yes, this is a welcoming place.

Neither Gary nor I were anxious to fish in the downpour (and I do have to confess that I am a fair weather angler these days), so we spent the afternoon in the lodge’s beautiful living room. As I got acquainted with Igor and Karen, and shared stories with them and other guests who had either arrived that afternoon or returned to the camps after a day of fishing, I found the afternoon flying by. I especially enjoyed perusing their wonderful collection of old books and hearing stories about some of the mounts on the walls.

Challenges

Igor and I talked about the challenges facing sporting camp owners these days, something I intend to write about soon. Finding staff is right at the top of the list and he told me a funny story about one fellow who applied for a job at the camps, emphasizing that, “I would be great because I love fishing!” You would be wrong if you think working at a sporting camp gives you a lot of time to fish. Igor and Karen had, up to the first week in June, fished just once this year, for two hours. Last year they fished for four hours, total.

We also talked about how they’ve had to add outdoor activities and special events to make up for the loss of the traditional deer hunting business. They once hosted 50 deer hunters each fall. Today, almost none. They do get a lot of bird hunters in the fall, are especially busy with bear hunters, and also host moose hunters, but their summers are now busy with families and special events, and they are fortunate to still be a major destination for anglers. Most of those return each year, often several times a year. Ninety percent or more of their guests have been here before. Forty percent of their guests are Maine residents. Karen explained that, “every two weeks is a new season here,” and looking at their schedule of activities, I had to agree. There’s a lot going on here!

Before we knew it, the dinner bell was ringing. Yes, they have the traditional dinner bell. Chef Tiffany, originally from Dexter and now living in Portland in the off-season, is a great cook. This far off the grid, and more than 50 miles from a grocery store, you have to be imaginative, and she is all of that. All of our meals were great, and my very favorite dish was her beef stroganoff.

With other guests at our dinner table the first night, we shared stories about loons grabbing our trout. I told my story about the bat that picked my fly right out of the air. I had to reel it in to release it. Both Gary and I had also caught ducks while fly fishing. Warden stories were interesting too, some good, some bad. By the time the dessert arrived – home-made vanilla ice cream with chocolate cookies and hot fudge sauce – well, I shouldn’t have done it, but I not only ate every bit of it, I licked the bowl!

And just to show you how tuned in the staff is to your every need, they keep the meals hot for guests who arrive late from fishing. Callie, our server, was very friendly and helpful, and Hannah, the Sikorsky’s God-daughter, who just graduated from college, was also on hand to tackle any and all jobs.

Breakfasts here are awesome and they’ll pack you a lunch so you can spend your day fishing, hunting, and enjoying the woods and waters.

Fishing

Igor is a pilot and flew Gary and me into Big Reed Pond for a day of very special day of fishing. About a third of their guests actually fly in to the camps. Jim Strang of Millinocket offers that service.

As Gary and I flew back from Big Reed that afternoon, Igor gave us a tour of the region, and I was astonished by how many remote ponds and flowages are available for fishing adventures. Gary has guided on all of them and he and Igor shared stories about each water as we flew over. Boy, did I want to jump out and try every one! Many are accessible by car, sometimes with a short hike after the drive. And Igor flies his guests into any of them for a day of fishing. He has canoes stashed at many and even cabins available at some. It would take a lot of visits to fish them all, but I discovered, while talking to the anglers who were at the camps at that time, that they all have a few favorites.

Anglers here are lucky because they still have good fishing for our traditional fish: brook trout, lake trout, and landlocked salmon. Many of their best brook trout waters are on the state’s Heritage List and protected, offering rare opportunities to fish for our native fish (Maine has 97 percent of the native brook trout left in the United States). Gary Corson – along with the Sportsman’s Alliance of Maine when I served as the organization’s executive director – led the campaign to win legislative approval for the initiative to name the brook trout as our Heritage Fish and protect them in 300 waters that have never been stocked and still hold native brook trout. The guests are Bradford were very clear on their desire to catch native and wild fish. They don’t come all the way up here to catch stocked fish.

David told us he likes to hike into remote ponds, and Igor gives him a radio to check in. He has a special affection for the guides here. And his voice got excited when he told me about the 23-inch trout he caught on his 3-wt. fly rod. I’d be excited too!

Guests

One thing I love about sporting camps is that you get to meet so many interesting people and always leave with new friends. David, for example, arrived just after us and joined us in the living room that afternoon, sharing micro-brews with me. I have to admit, despite my affinity for Maine micro-brews, David’s All Day IPA session ale from Founders in Grand Rapids, Michigan, was very good. David first came to Bradford to hunt grouse and still does, telling me the grouse hunting is amazing here. Eventually, he started coming here to fly fish (and he has fished in a lot of other places, including some of my favorites in Montana).

Gary and I got up at 5:30 am each of the two mornings there, and were welcomed into the kitchen where coffee was ready and Igor, staff, and some guests were enjoying the early morning. I could get used to this!

While we were in the living room the first afternoon, a guest came in from fishing, very excited. He’d caught his biggest brook trout ever, with his new Orvis 5-wt. rod.

Another guest told me he plans to bring his five grandchildren here. “It’s a good place to introduce them to hunting and angling in a comfortable and safe place,” he said.

I really enjoyed one guest’s story about the time he was bird hunting here and lost his dog. Igor took off in his plane and searched for the dog that night. They put out a kennel and the dog’s blanket near where he’d last been seen, and someone found the dog and put him in the kennel.

David had a great story about a friend who landed 40 fish someplace (not here), but came out of the water at the end of the day covered in leeches. And I was captivated by his stories of grouse hunting here, when he rarely ever sees another hunter. “If you are willing to walk,” he said, “there are endless covers.”

Karen likes to talk with all new guests, before they arrive, to make sure they know what to expect and that their expectations are met. A good policy, for sure.

Leaving

On our final morning, Igor gave me a tour of the cabins, his workshop, the new $6000 generator, the sawmill, and the bridge he built across the brook so Brad Hall, their neighbor, could walk over to visit. Brad’s father once owned the camps and we had a great visit with him that morning. I was very interested to discover that Brad has solar power at his camp. His apple trees, like Igor’s and Karen’s, were devastated by hungry moose.

The ice house was particularly interesting. Every winter, Igor and 6 to 12 friends come up to cut the ice and store it under sawdust in the ice house. They stay in one winterized cabin that even has hot water. One guy brings his own beef. They cook. They snowshoe. They snowmobile in. They cut the ice into large blocks and swing them into the ice house with a special contraption. They used to have to lift them in and I guess that was pretty tough. I stuck my hands into the sawdust and felt the very cold ice, understanding that it lasts until the end of October.

I laughed when we entered Cabin 8, everyone’s favorite, at the end of the line of cabins, and then noticed Cabin 1 next to it. While the some of the cabins have been relocated, they kept their numbers for guests who always want the same cabin for their visits here.

Behind Cabin 2, a big old pine was hit by lightning one night while everyone was at dinner. The lightening went into the ground and connected to the gas line under the cabin and the tree caught fire. It burned for about a half hour, when a guest ran to the lodge and told Igor, “You’ve got to come now!” He shut off the generator, cutting off the propane, and the fire went out.

So many great stories here. And I perked up when they started telling stories about Jerry Bard, who worked here for 25 years, but before that, worked at Camp Phoenix, where I now own a camp. After 100 years as a sporting camp, Camp Phoenix was turned into a condominium. It reminded me of how lucky we are to still have Bradford Camps and the few dozen other sporting camps that have been able to transition to this new day and economy, while maintaining such a wonderful and timeless tradition.

Written by George Smith, June 16, 2015 – http://georgesoutdoornews.bangordailynews.com/2015/06/16/hunting/bradford-camps-are-a-state-treasure/