Maine Sporting Camps began to appear in the mid 1800’s as entrepreneurs responded to a growing demand by the ever increasing city dwellers for natural recreational activities that could provide fresh air, clean water and open vistas.

When Maine became a state in 1820, lumbering and the country’s industrial heyday were already in full swing. Cities like Boston, New York and Philadelphia were growing tall, crowded and polluted. By 1850, when Henry David Thoreau was making his historic trips from Boston into the Maine woods, the industrialized city dwellers had an increasing amount of free time and started to spawn a new industry – nature tourism. Entrepreneurs in Maine responded by building seaside resorts, and for the more adventurous tourists, Maine Sporting Camps began to appear.

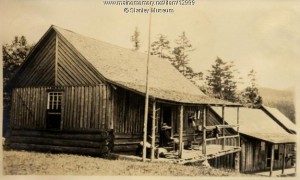

At that time, Maine’s great northern forests were fully occupied by the lumber industry, but had yet to experience any real estate development or tourism industry like we have today. The first sporting camp owners were able to pick the best locations – typically those having good fishing, good hunting and great scenery. And those places are still occupied by sporting camps today.

These vital characteristics, good fishing, good hunting and great scenery, had been discovered centuries, perhaps even thousands of years, ago by the people we know today as the Wabanaki Indians. The Wabanaki recognized the specialness of Maine’s land and water features, and incorporated them into their legends. Throughout Maine you will see Wabanaki names for the lakes, rivers and mountains.

One special place is Spencer Pond, site of Spencer Pond Camps, just east of Moosehead Lake, Maine’s largest. This spectacular setting remains unchanged since the ancient Wabanaki spirits shaped Maine’s landscape. A second sporting camp, Kokadjo Camps, is located at Kokadjo, on First Roach Pond.

The following Wabanaki legend, as told by the Penobscot Nation’s cultural historian, James Francis, beautifully illustrates the specialness of the area and how their names came to be.

The Legend of Gluscape and the Moose

This story is about how Gluscape (pronounced “glue-skaw-buh”) slew a cow moose and then chased its calf, creating place names from Mount Kineo all the way to Penobscot Bay.

The giant Gluscape is the benevolent culture hero of the Penobscots Indians who taught the people the arts of civilization and protected them from danger. This legend takes place in the winter, and Gluscape wanted to show his people that the moose was edible.

Gluscape came to Moosehead Lake and spied two moose, a cow and calf. He slew the moose, and its body became Kineo (“high bluff”). Now motherless, the moose calf began to run, knocking over the kettle Gluscape had been using to cook. The kettle became “Kokad’jo” (formed from kok, “kettle,” and wadjo, “mountain,” ie. “Kettle Mountain”), now commonly called “Little Spencer Mountain.”

Spencer Pond Camps is located on the shore of “Kokadjeweemgwasebemsis” (“little kettle-shaped mountain lake”). The nearby Kokadjo Camps are located on the shore of “Kokadjeweemgwasebem” (kettle-shaped mountain lake), commonly known as “First Roach Pond.”

In hot pursuit of the moose calf, Gluscape threw down his pack, which became “Sabota’wan” (“the end of the pack, where the strap is pulled together”), now called “Big Spencer Mountain.”

[As you can see in the photos, Little Spencer Mountain, the “kettle” or “Kokad’jo” is quite round, while “Sabota’wan” (Big Spencer Mountain) is long, and its top level, the eastern end being squared off much like the end of an Indian pack basket.]

With snowshoes strapped to his feet, Gluscape continued to chase the calf across the frozen landscape. All the while, Gluscape’s dog had been running behind him, but when Gluscape jumped over Penobscot Bay, the dog couldn’t make the leap and the two became separated.

When Gluscape reached Cape Rosier, he killed the calf and threw his dog some of the moose’s entrails, which landed in the water. They became landscape markers and were given names representing their color and shape. Cape Rosier (“Mosikatcik”) became known as the moose’s rump.

Thrumcap Ledge (“Osquoon”), east of Cape Rosier can be seen due south of Orcutt Harbor. The rock is known as Osquoon, meaning “the liver.” It is a marker for the entrance to an ancient portage route through Horseshoe Cove.

The moose’s entrails can still be seen today as a large vein of white quartz that runs under the water. “If you travel across the bay, you’d go right to that,” Francis said. “It’s very visible from quite a distance.”

Gluscape also left his own mark on the landscape. When he landed after jumping the bay, his snowshoes left prints in the rocks at Dice Head in Castine. Veins of white quartz that run through the ledge there have the appearance of snowshoes cast in the rock. “You have to use your imagination, but I can see why they would say that for that place,” Francis said.

In another version of this legend, when men like Gluscape and animals grew to an immense size, the Indians thought that a moose was too large to hunt. They asked Gluscape to make the moose smaller. He killed a big bull, becoming Kineo Mountain, and reduced his size by cutting slices from his body. The rook at the foot of the mountain today looks like steak; streaks of lean and fat can be plainly seen in it. The hunter cooked his meat, and afterwards turned his kettle, Little Kineo Mountain, on its side, and left it to dry. So the moose grew smaller and smaller, and the Indian people were able to hunt it.